Can Judges from the Florida Supreme Court get a Reasonable Accommodation for a Disability?

By: Matthew Dietz

On Monday, September 14th, Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Jorge Labarga, 62, underwent successful surgery for kidney cancer at Shands Hospital in Gainesville. Doctors had discovered the cancer in its early stages through routine blood tests earlier this year. They advised him to have the kidney removed. Justice Labarga was expected to be hospitalized for seven days. However, after surgery, Justice Labarga began working at his job remotely, with Barbara Pariente, another cancer survivor, serving as acting chief justice during any time he is incapacitated. According to the Court, “Doctors found no signs that the cancer had spread and predict a full and quick recovery for Florida’s 56th Chief Justice and its first of Hispanic descent.”

When Justice Barbara Pariente underwent her battle with breast cancer in 2003, she had a 14-hour double mastectomy and reconstructive surgery. After choosing an aggressive treatment and chemotherapy, Justice Pariente continued to sit on the bench while she was undergoing her cancer treatment. She decided to bare her soul and her scalp from the bench when she decided that she was not going to hide the fact that she had cancer:

During Pariente’s liberating courtroom debut, sans wig, there was a Supreme Court ceremony to induct new members to The Florida Bar. In his speech, then Bar President Miles McGrane made references to heroes in the law Atticus Finch and Chesterfield Smith. And then with a nod to Justice Pariente, he said, “I am so honored and pleased that you are doing what you’re doing for your cause. You are a hero to me, and, I think, everyone here.” Clearly touched by his remarks, Pariente’s eyes glistened with tears as the spectators broke into applause.

According to Eleanor Hunter, executive director of the Florida Board of Bar Examiners, Pariente never missed an oral argument throughout her cancer treatment. She also participated in all conferences, including one by telephone and one video conference. Hunter said: “The most remarkable thing to me is while she sat at chemotherapy, she took a briefcase of her work, reading over cases and briefs, with an IV dripping in her arm.”

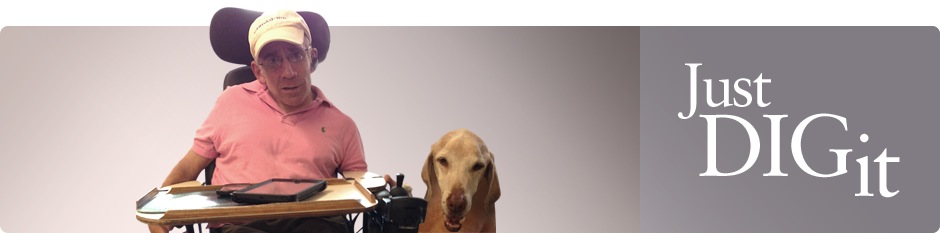

Work was not even a question for either Justice Labarga or Justice Pariente. It was what each chose to do. Last month, the DIG newsletter contained an article about the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s new case with DIG client Gregorio Reyes, who was fired from his job while he was recovering from prostate cancer. In all pronouncements by the Supreme Court and the press, the fact that the Justices were returning to work, and that they were able to continue their jobs with a minimal accommodation, appears merely to be an afterthought. While it may be an afterthought for the Florida Supreme Court, it is not for most employers who view cancer and chemotherapy as a reason to question an employee’s ability to work during and after cancer treatment.

Even when the prognosis is excellent, like that of Justice Labarga, some employers expect that a person diagnosed with cancer will take long absences from work or be unable to focus on job duties. The Americans with Disabilities Act protects persons who currently have cancer, or have cancer that is in remission, because they are substantially limited in the major life activity of normal cell growth or would be so limited if cancer currently in remission was to recur. (See 29 C.F.R. §§1630.2(j)(3)(iii) and 1630.2(j) (1)(vii)). However, cancer is not identical for all persons, and the symptoms and side effects depend on many factors, including the primary site of the cancer, stage of the disease, age and health of the individual, and type of treatments. The most common symptoms and side effects of cancer and/or treatment are pain, fatigue, problems related to nutrition and weight management, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, low blood counts, memory and concentration loss, depression, and respiratory problems.

If an employee reveals that he or she has or had cancer, the employer may not ask any questions about the condition, unless: the employer reasonably believes that he or she will require an accommodation to perform the job, the employer observed performance problems, and the employer reasonably believes that the problems are related to a medical condition. In any event, any inquiry or discussions should remain confidential.

For a lawyer or a judge, the accommodations necessary to do the job are relatively simple. The accommodations include working (or even appearing at hearings) from remote locations, allowance of breaks, or a rest area during the day, and time off to go for treatment or to the doctor’s office.

There are other protections that may be available, such as Family and Medical Leave Act, 29 U.S.C. § 2601, and some law firm or other state laws, which may provide medical leave for larger employers or governmental entities.

So, accommodations for a disability is readily achievable for any lawyer.

For more information, see

Questions & Answers about Cancer in the Workplace and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Accommodation and Compliance Series: Employees with Cancer

Reasonable Accommodations for Attorneys with Disabilities, by Matthew W. Dietz

All of the history of Justice Pariente’s condition is from Jan Pudlow’s 2004 in the Florida article – Barbara J. Pariente, Chief Justice of the Florida Supreme Court

.